We will review the data and determine the next steps for the program—

December 2019. May 2022. June 2024. Much has gone on each time Starliner journeys to space before reaching the ground once again, but ultimately, the fact of the matter is that Boeing and NASA have launched and returned Starliner to Earth, uncrewed and successfully, three times.

But Starliner isn’t a cargo spacecraft. NASA’s Steve Stich put it best on July 25th during a news conference: “Starliner was designed as a spacecraft to have the crew in the cockpit … The vehicle is really set up to work with the crew.” He is referencing Crew Dragon’s stark contrast in the underlying functional design and background of SpaceX, being nearly an all-glass, touchscreen cockpit and having 8 years (nearly to the day: May 25, 2012 – May 30, 2020) of experience delivering autonomous cargo Dragon rendezvous flights to the International Space Station.

full-res download, wall print, or commercial license this image

Starliner launched most recently on June 5, 2024 with two NASA astronauts aboard… why didn’t Starliner round out their space odyssey?

Whether you’re just joining in, or have a seasoned understanding of spaceflight, I encourage you to view the circumstances which brought us to this moment from a middle point of view. At the same time, also take into account the context of the Boeing effort, NASA’s many considerations, and the current state of the Commercial Crew Program as a whole.

The goal of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program is “safe, reliable, and cost-effective human transportation to and from the International Space Station, from the United States, through a partnership with American private industry.”

Brief Summary—

How it started:

- OFT (2019 – uncrewed)

- CFT (early 2021 – 2 crew)

- Starliner-1 (4 crew)

- Starliner-2 (4 crew)

- Starliner-3 (4 crew)

- Contract options for Starliner-4/5/6

How it’s going:

- Dec 2019: OFT-1 (uncrewed)

- May 2022: OFT-2 (uncrewed)

- June 2024: CFT (2 crew)

- Starliner-1 (2025)

- Starliner-2 (2026)

- Starliner-3 (2027)

- Contract options for Starliner-4/5/6

Pre-launch prep for anyone still in processing—

In December 2019, during Starliner’s very first mission (now known as OFT-1), software was not configured properly for the spacecraft to understand where it was in the mission timeline. When separating from Atlas V, the craft’s clock was some 11 hours off. This resulted in Starliner keeping its foot on the gas for far too long, at the wrong time, and thus, being unable to reach the International Space Station to test out autonomous rendezvous and docking capabilities. This lapse was, understandably, great enough that NASA required Boeing to take a second swing at OFT.

Starliner OFT-2 in May 2022.

Photos: Trevor Mahlmann | full-resolution download, wall print. or commercial license of these images

Starliner’s second flight, following original timelines, would have been Crew Flight Test. In July/August of 2021, Starliner was on the launch pad prepared for flight, only to discover a multitude of stuck valves. This delayed OFT-2 further to May 2022, where Starliner would launch to build upon the list of objectives completed during OFT-1 and executing a full mission rehearsal.

During both OFT missions, though, there were numerous issues that NASA and Boeing needed to work together to overcome, before moving forward with the CFT.

For example, on OFT-2, there were two OMAC (Orbital Maneuvering and Control) thrusters that “failed off” during an orbital insertion burn. These OMACs would become a recurring problem for Boeing and NASA.

Later, in June 2023, when CFT (the now-third flight of Starliner) was scheduled for July 21, 2023, parachute issues were discovered in addition to “over a mile” of flammable tape, Mark Nappi, VP and Program Manager of Boeing Starliner, later said in a March 2024 telecon. These Summer 2023 findings both set the prefatory crewed mission back indefinitely.

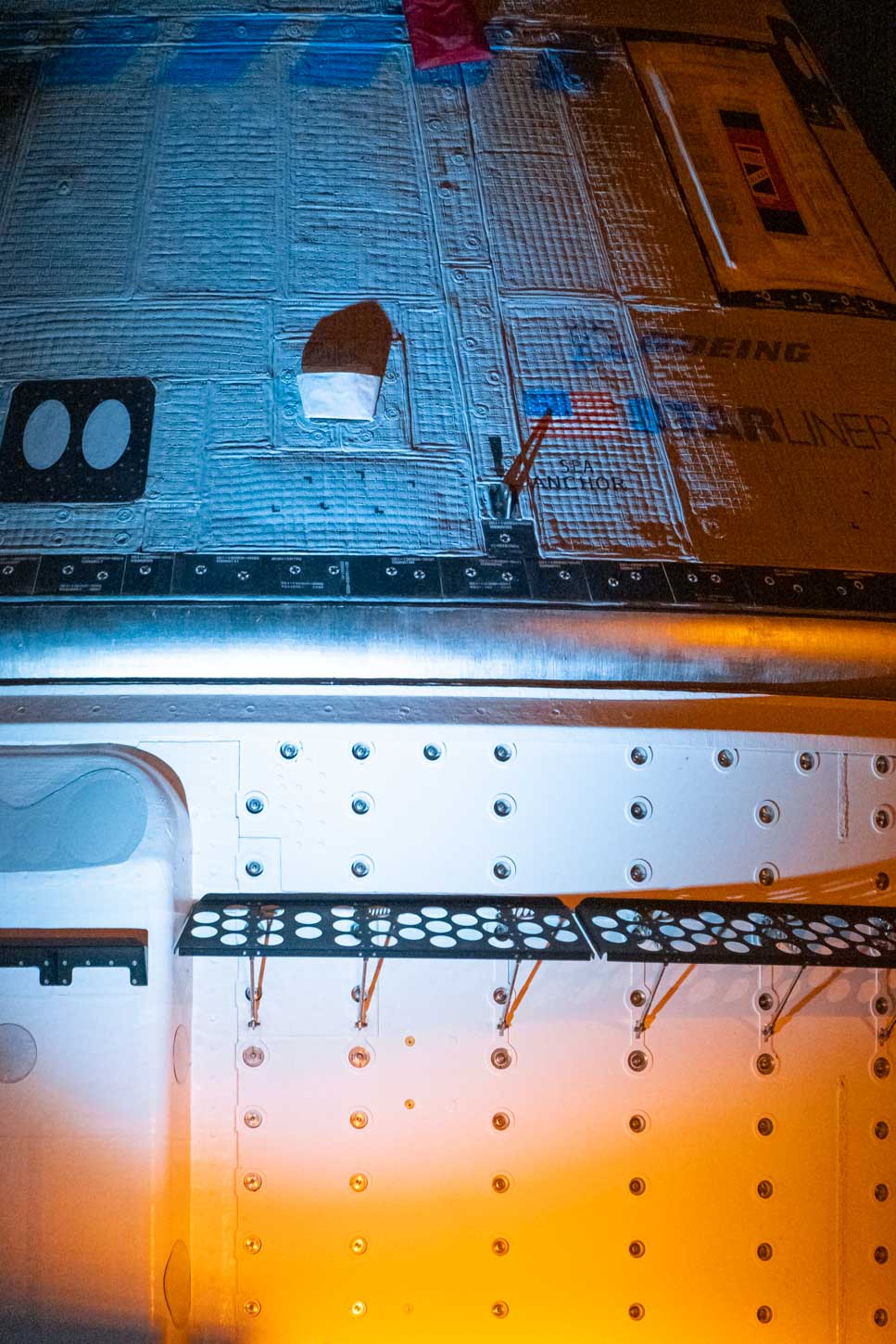

Photo: Trevor Mahlmann |

full-resolution download, wall print, or commercial license of this image

Finally, after rollout to the launch pad in May of 2024, flight controllers powered up Starliner to find a helium leak in the spacecraft. Determining that this single leak and its rate were small enough to handle in-flight (even in a worst-case scenario), NASA proceeded with the launch.

Eventually, on June 5, 2024, Crew Flight Test, after being delayed nine times over the course of multiple years, some spacecraft-related and some not, lifted off with Butch and Suni aboard, headed for the ISS.

Finally, NASA and Boeing could put the setbacks behind them and begin anew… right?

Unfortunately not.

8 days turns to 8 months—

Hours after launch, controllers would come to discover two more leaks (one of which was relatively large, at 395 psi per minute), then a fourth and shortly after docking, a fifth was referenced by NASA’s Steve Stich.

The key notion with these leaks was that Boeing could stop them from happening altogether if they disabled the propulsion system. Helium is used as a pressurant to move fuels through the system. After extending the initial 45-day period Starliner was certified for at ISS, and disabling the helium manifolds, this gave NASA several summer months to conduct in-depth analysis into the situation and the spacecraft’s health.

Before CFT took off, NASA and Boeing both mentioned, many times, how CFT would last eight days. They were also keen to mention this was a test flight, but repeatedly characterized the brief nature of the mission.

After Starliner’s launch, NASA and Boeing shied away from openly communicating how and when Butch and Suni would return, and were often vague in answering questions regarding what needed to be done before doing so, beyond saying they were trying to understand more about the thrusters and simply needed additional time.

These two decisions would each end up boomeranging to negatively impact the public sentiment surrounding the mission, compounded by compassion for two astronauts now in space without the ability to come home, for much longer than originally planned. They are astronauts and test pilots, of course, and were likely keenly aware of the potential for problems to arise, potentially even problems like this, but this was quite a shake-up in the plan.

Photo: Trevor Mahlmann

full-resolution download, wall print, or commercial license of this image

These discussions went on for most of June, July, and August. Their return was continually delayed. Starting in mid-June, the return was moved into July, late July, August, and mid-August. It was supremely clear Boeing and NASA were having quite a difficult time reaching congruence on flight rationale to safely return two astronauts to Earth or “reasons why a particular space mission is considered acceptably safe to carry out” as Wayne Hale, a Space Shuttle Program Manager and Flight Director for 40 missions, puts it.

NASA, in July, without initially keeping Boeing in step with their plans, worked with SpaceX behind the scenes to prepare contingency options for Butch and Suni to fly home on the next Crew-9 Dragon, SpaceX’s already-planned operational flight of four crew members launching in the fall of 2024 and returning to Earth in early 2025.

On August 7th, in a news briefing conducted by Ken Bowersox (current associate admin. for NASA’s Space Operations Mission Directorate, former NASA Astronaut and Naval aviator), the fruits of these labors with SpaceX became known. A contingency possibility was shared where two (instead of four) crew would fly to ISS on Crew-9 Dragon, an operational ~6-month mission would be carried out, and Butch and Suni would join them in a tried-and-true Crew Dragon, returning to Earth in February of 2025. This would, however, not be without additional risk in some ways.

“We don’t just have to bring a crew back on Starliner, for example. We could bring them back on another vehicle,” Bowersox said on August 7th. NASA continually mentioned how their primary focus was to return crew on Starliner, but they repeatedly put forward that if SpaceX were needed, the initial task order work was complete should that path be necessary.

NASA’s Dana Weigel (NASA ISS Program Manager) described that this work with SpaceX initially began as a contingency to bring home NASA astronaut Tracy Dyson, in the event of a Soyuz coolant leak similar to previous incidents.

Steve Stich later added that “…as our [NASA] community, I would say, got more and more uncomfortable with the uncertainty in the thrusters [on Starliner] I think that, to me, upped the priority in having this capability in place.” The focus and purpose, even if it began via other means, was quickly changing.

This was the beginning of the end for Starliner returning home with Butch and Suni. Boeing was supplying the modeling they thought was relevant to safely return them home. NASA was continually finding new items of concern that were not in harmony with Butch and Suni’s safe return, be it swelling Teflon seals, thruster recovery timing, or otherwise.

Key quotes—

In both cases: whether via Starliner return, or Crew-9 Dragon cargo, risk to Butch and Suni would go up. “You have to really dig-in to understand what the baseline risk change is.” Bowersox noted on August 24th, comparing the two options. “That’s what the team has been working so hard this last couple of months [on].” This begins to explain a lot of what initially felt, from all sides in working with NASA, like poor communication and lack of ongoing teleconferences. Teams were just incredibly busy navigating uncharted waters.

Having begun down this path over a decade ago to build up the commercial capability to get American astronauts to space on their own accord, NASA is in an unprecedented place with two commercial, crew-capable vehicles. They have now and are in a “problem” (blessing in disguise) of their own creation.

NASA has incredible flexibility on the table in Starliner and Crew Dragon that they’ve simply never truly had before. The Commercial Crew Program exists so that we don’t need to rely on other international partners to get our astronauts to space. And now we’re here, or nearly there.

“We just don’t know how much we can use the thrusters on the way back home [on Starliner], before we encounter a problem, because of the heating effects that happened on the way uphill.” Bowersox continued in the August 24, 2024 telecon.

Photo: Trevor Mahlmann

full-resolution download, wall print, or commercial license of this image

If you read no other section, read this one—

Stich followed Bowersox: “We had some thruster experts come in and talked to us a few weeks ago. We are clearly operating this thruster at a higher temperature at times than it was designed for. Could a thruster just fail off gracefully or could there be another failure mode that is not so graceful?”

Steve carried on: “For some reason, the heating is higher in that starboard doghouse that we do not understand. When an OMAC thruster fires, the other thrusters [in that cluster of five] get heated at a much higher rate than expected.”

He explained in-depth that NASA is well-aware of damaged Teflon seals in the thrusters that are made worse or further damaged through continued operation. They found this out through parallel testing at White Sands in July. He posed the question “how close [are] we to a cliff?”The questions at stake: Will the Teflon damage present faster than it did during docking, where they had multiple thrusters fail? What corners could Boeing, NASA, Starliner, and its two-astronaut crew be backed into if these failures happened faster than they expected? Undocking and de-orbit burn is a relatively less demanding environment overall, but it is still a rapid succession of thruster firings.

These were all things NASA expertly sought answers to and was not getting concrete feedback on. Nor were they going to. The service module cannot be serviced in orbit, and it would burn up in the atmosphere upon reentry.

The gaps in knowledge and understanding were simply too great. NASA could not wisely put its astronauts aboard Starliner and ensure they were taking the best option for a safe return. During this same briefing on August 24, NASA announced its decision: Boeing Starliner would come home uncrewed with Butch and Suni flying home on Crew-9 Dragon in February 2025.

Photo: Trevor Mahlmann

full-resolution download, wall print, or commercial license of this image

What’s next?—

This ongoing situation has placed the Boeing Commercial Crew effort in a difficult position. NASA has only committed to three operational flights of Starliner. As best I understand it, the plans were for Crew Dragon and Starliner, once both operational, to switch off every 6 months. Starliner-3 is then reached in 2027 or 2028 after Starliner-1 in 2025. This also assumes no other hiccups along the way before Starliner’s next flight.

Russia has committed to the ISS and its operations until 2028. The U.S., Japan, Canada, and ESA member states have done so through 2030.

NASA recently announced that SpaceX had won a contract to de-orbit the ISS in the 2030 timeframe.

All of this to say, Starliner’s delays and difficulties to date don’t offer it great flexibility in winning any further flights. Time is running out, at least for this ISS to be Starliner’s destination.

Trevor’s take—

It’s so encouraging to have seen NASA, second-hand, work through the process the way they have. These developments are indicative of an incredibly healthy communication process and culture present within the organization. It is indeed difficult at times to be on the slow drip of information, but I think it’s important to keep both of these front of mind.

Putting it into perspective, though, here is how NASA ultimately viewed the risk of crew returning in Starliner on this mission. Starliner was Butch and Suni’s lifeboat. There are two places crew spacecraft can dock to on the ISS. Crew-8 Dragon and CFT Starliner were both docked. Starliner had to leave, and Butch and Suni were staying put, before the next Crew-9 Dragon could launch and dock.

So, there would be a window of time where Butch and Suni would need a temporary lifeboat.

It was a very small chance of actually being used, but NASA put into place a six-crew return contingency capability on the Crew-8 Dragon spacecraft (launched in March, before Starliner) wherein, Butch and Suni would be strapped in below the four operational seats, without spacesuits, in the mid-deck, to the cargo pallet inside Crew-8 Dragon. In the event they needed to immediately depart the orbital outpost, strapped into a cargo pallet of Dragon would be their lifeboat.

NASA thought it more risky to return Butch and Suni in Starliner, with pressurized suits and in seats tailor-made for them, than unsuited inside Dragon. I say this not to dramatize the decision or to counter NASA’s thoughtful review, but to characterize and provide powerful perspective of how NASA themselves understood and classified the level of risk of returning to Earth inside Starliner.

Photo: Trevor Mahlmann

full-resolution download, wall print, or commercial license of this image

The human perspective—

The most recent time where Boeing personnel have been present on media teleconferences regarding CFT was July 25. In the August 7 telecon, Ken Bowersox mentioned “we’ll have chances to bring Boeing back along with SpaceX in the future as we progress.”

With SpaceX’s heavy involvement now in returning Butch and Suni home, and NASA and Boeing’s clear lack of congruence on the best path to take, these are noteworthy omissions. But again, these teams are busy conducting brand-new orchestras.

After Starliner had successfully returned without its crew, NASA held the most recent teleconference at 1:30 a.m. ET, ninety minutes after successful touchdown at White Sands. Boeing was still not present on the call. Joel Montalbano was asked why, and responded saying “We did talk to Boeing before this. They deferred to NASA to represent the mission.”

Mark Nappi, Vice President and Program Manager of Boeing’s Commercial Crew Program, in an update after the landing, said “We will review the data and determine the next steps for the program.”

Steve Stich continued on the telecon: “You know, from a human perspective, all of us feel happy about the successful landing, but then there’s a piece of us, all of us, that we wish it would have been the way we had planned it. I think there is, depending on who you are on the team, different emotions associated with that.”

A difficult situation to navigate, for sure.

NASA has been clear: Starliner will fly again, it’s just going to take a bit of time to get there. Starliner just does not have a lot on time on its hands, and fulfilling this duty to NASA are where these complex, passionate feelings and emotions come into focus.

I recently read “Getting to Yes” at the recommendation of a great friend. If you haven’t read it, please do. It has many methodologies and perspectives which can be utilized to more effectively navigate every facet of your life on this Earth working with other people.

In the book, it reads “Give positive support to the humans on the other side, in equal strength, to the vigor with which you emphasize the problem.”

Photo: Trevor Mahlmann

full-resolution download, wall print, or commercial license of this image

This is a great mantra not just for NASA, but for everyone. If NASA and Boeing can carefully navigate these future uncharted territories together in this manner, being hard on the problem, but not on the people, Starliner has a bright future ahead of it fulfilling its duties to NASA over the next half-decade.

See you back out on the launch pad soon, Starliner.

Each of the photos and all of the writing in this story, is my own. I’m currently a self-employed photojournalist navigating my own uncharted territory.

If you’d like to see more stories like this, the best way to support this passionate work of mine is to pre-order my Wall Calendars here:

Thank you for your consideration and support!

Want stories like this in your inbox?

Leave your email below to keep up-to-date with the latest in spaceflight! (A few emails a month, max.)