Reduced, asymmetric thrust, compensated well by the rocket’s robust—

CAPE CANAVERAL, FL — At 7:25 a.m. EST, United Launch Alliance flew its Cert-2 mission. Aptly named, this was the second in a series of Vulcan certification flights and the latest in a string of successes for the storied space company.

Though Vulcan, new on the scene as of this year, first needs to prove out its capabilities.

Space Systems Command, a key division of the U.S. Space Force who acquires reliable and resilient space launch, requires that an in-depth certification process of the design and performance of launch systems take place before permitting companies like ULA to carry its clandestine satellites to orbit.

Part of this process is having several successful flights under its belt. Vulcan Cert-1 flew in January 2024, carrying the Astrobotic Peregrine lunar lander. Although the lunar lander experienced an anomaly which would not allow it to complete its primary mission of landing on the Moon, the flight of the rocket that brought it to space was without fault.

Cert-2 this morning stands to be the next success in ULA’s arsenal of 100% mission success. However, this 100% success badge they proudly wear is not without close calls or near misses.

In 2016, during an Atlas V mission launching a Cygnus resupply spacecraft to orbit for Northrop Grumman, the rocket experienced an anomaly where the first stage shut down around 6 seconds early. This caused the Centaur second stage to burn for nearly an extra minute to make up the velocity shortfalls. ULA considered this event an anomaly and began an investigation into the root cause.

ULA had an idea of what the cause could be, but was reserved in sharing many details. CEO Tory Bruno said at the time, in a comment on Reddit:

“By approaching investigations in this disciplined manner, you have the highest confidence of arriving at a complete, global, and permanent corrective action.”

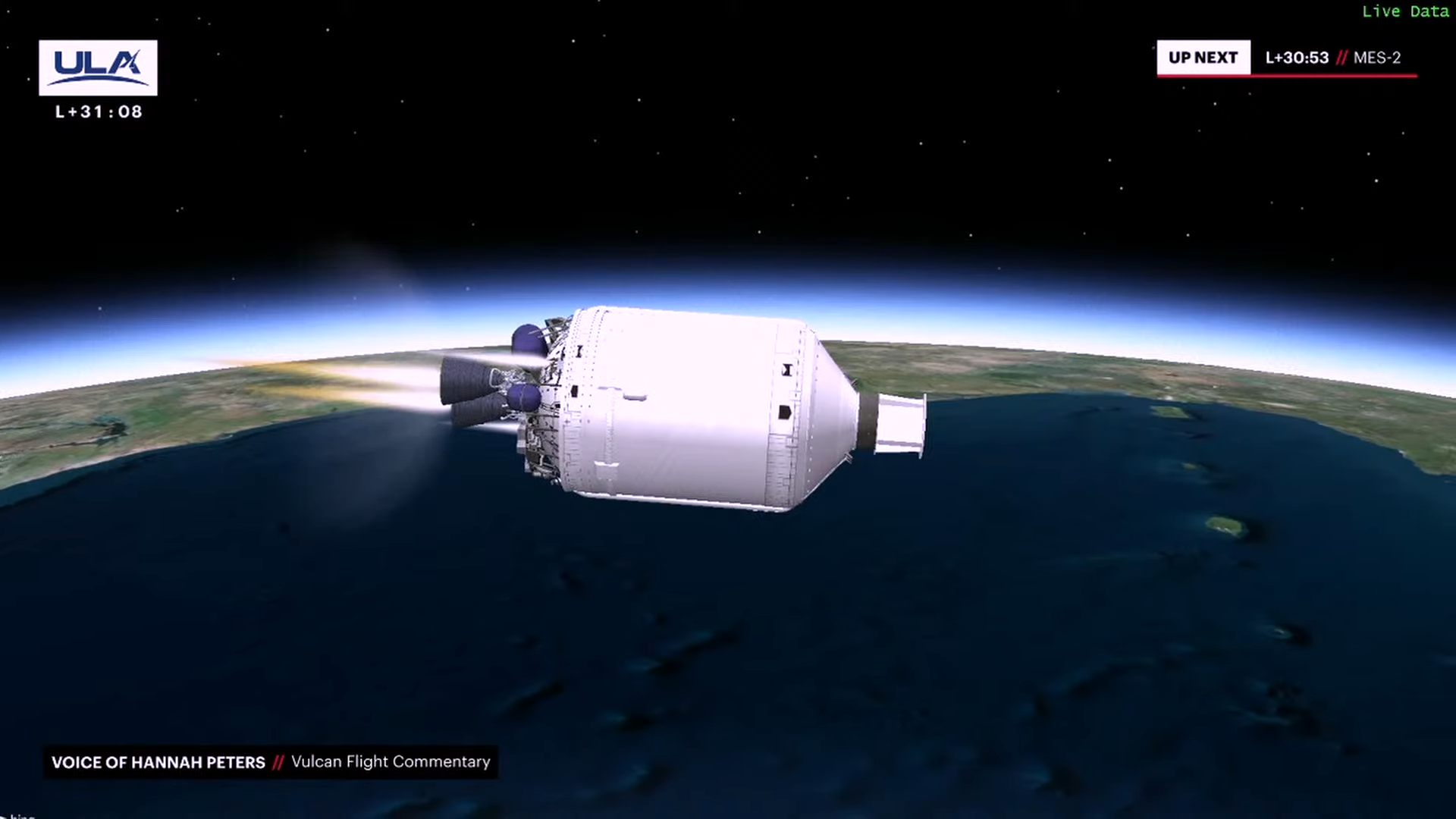

CERT-2

38 seconds into flight of Vulcan this morning, near the base of one of the rocket’s solid rocket boosters, an abnormal detonation or blowout of material occurred, which looked to take with it the nozzle of the booster.

Moments later, as the live feeds cut to another camera, you could see the asymmetric thrust from the right SRB emanating sideways and more widely outward than the other.

On-screen, SRB jettison was to occur at 1 minute 49 seconds into the mission. A pre-launch graphic shared on social media specific to Cert-2 aligned with this timing. SRB jettison, however, didn’t occur until nearly 20 seconds after that.

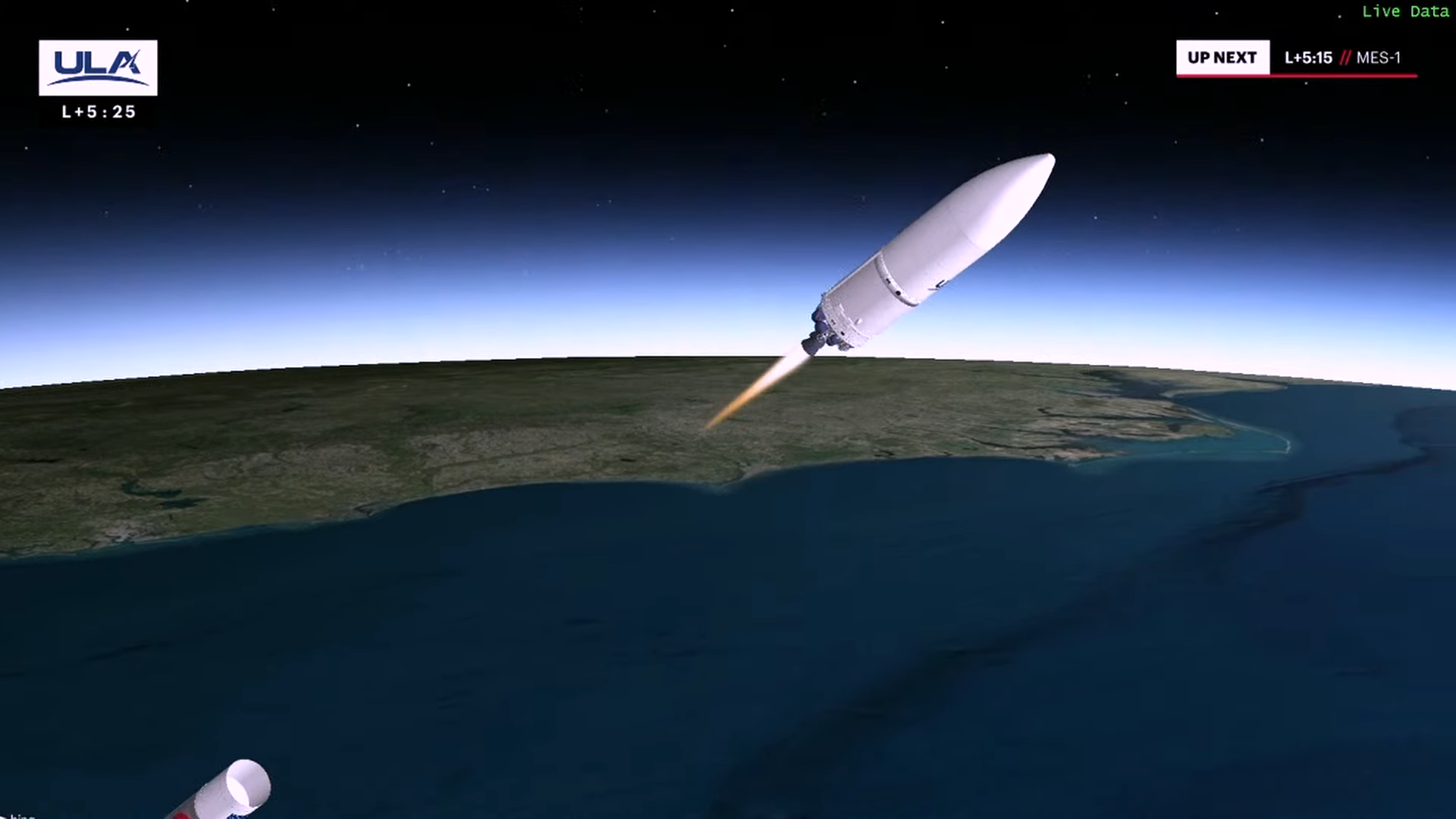

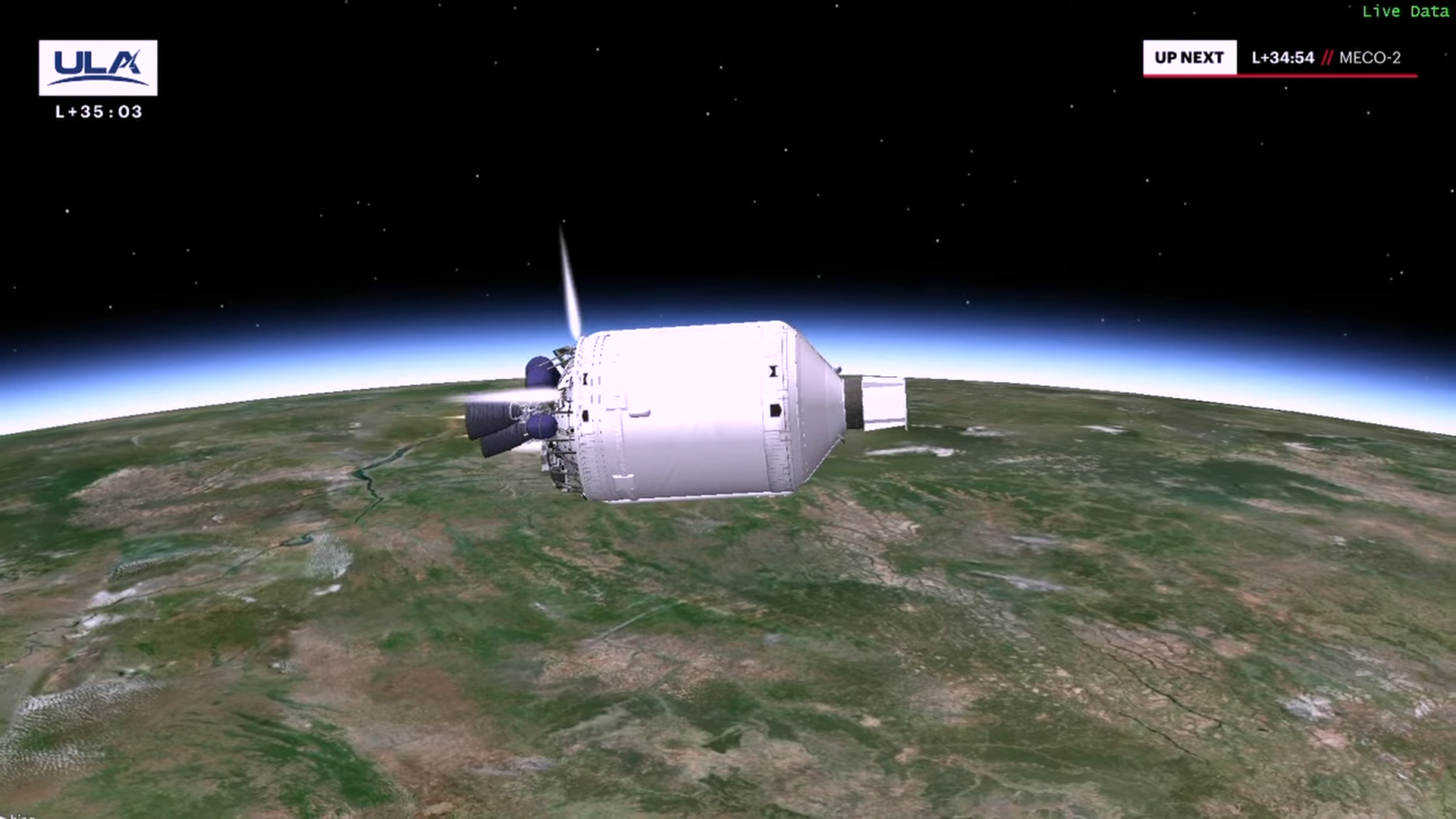

Centaur MES-1(First Main Engine Start of the second stage) was to occur at T+5:15, and occurred about 10 seconds behind. Did the first stage of Vulcan, fit with its dual Blue Origin BE-4 engines, burn slightly longer to make up for the difference?

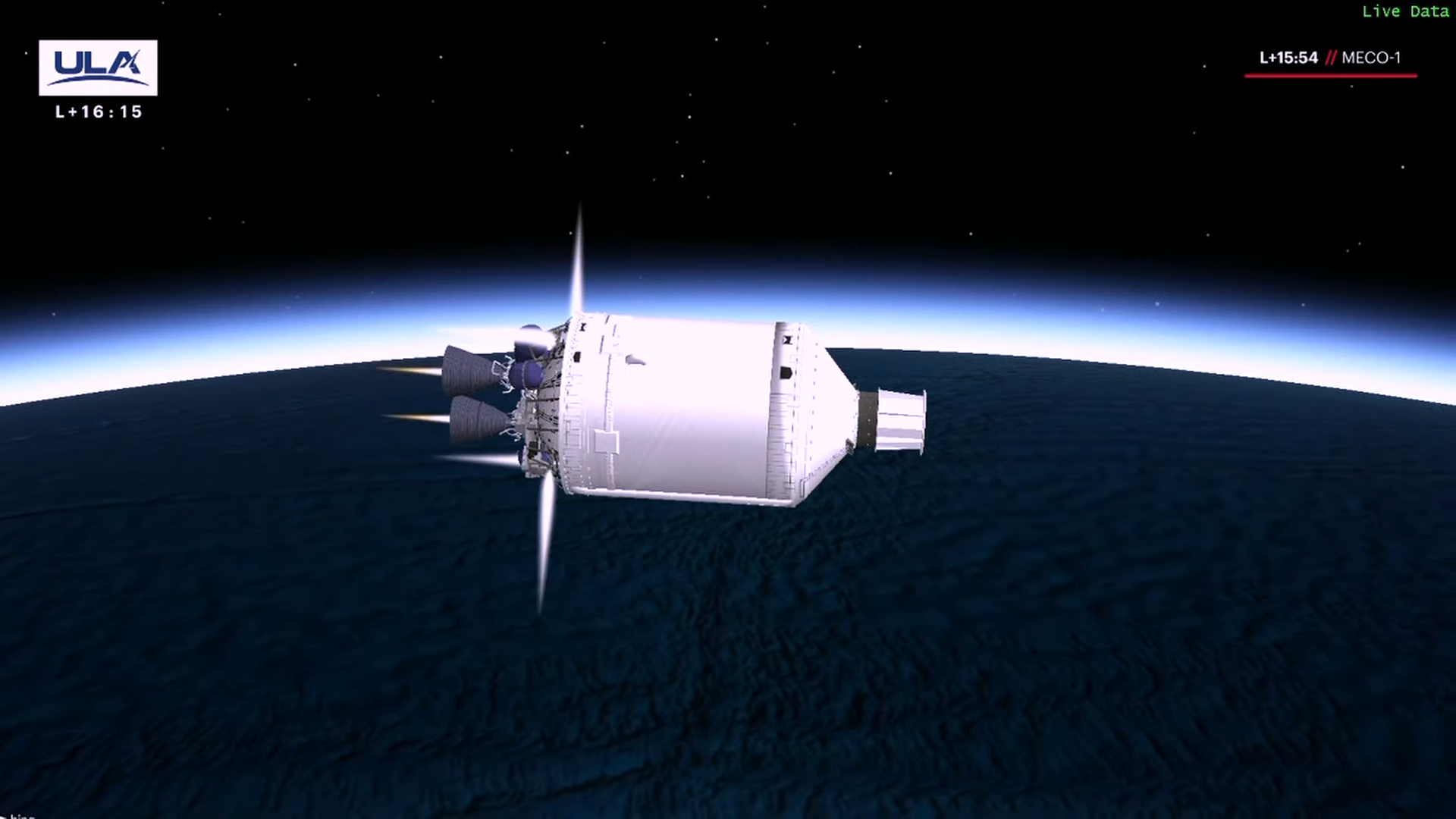

Similarly, MECO-1, MES-2, and MECO-2 of Centaur occurred with similar deltas to the original plan at about 21, 15, and 9 seconds, respectively.

United Launch Alliance

From a bystander’s perspective, the decreasing impact to the planned burn lengths and times, it seems like Vulcan’s first stage and Centaur upper stage worked together to successfully overcome the abnormal thrust profile of the SRB and get the vehicle back on track.

Through time, the first stage of Vulcan burned nearly the shortest amount of additional time, but it also imparted much more thrust than Centaur during its burn. When Atlas V’s first stage cut off early by 6 seconds, it translated to nearly a minute of extra Centaur burn.

Tory Bruno explained this post-launch in a few posts on Twitter:

Think of it like slices of a pie. For easy numbers, 80% of the pie is allocated to the primary mission. 10% of the pie for propellant reserves, and the final 10% for propellant margin.

Over 200 launches in, and I learn something new too: the difference (at least with ULA) between how they classify propellant reserves and propellant margins.

During the Cert-2 mission, it used up all of the 80%, some of the 10% of reserves, but none of the 10% of margin, by this analogy.

The abnormal SRB nozzle event, and the reduced, asymmetric thrust it caused ate up some overhead from the reserves, but not all of them. Propellant margin on top of these reserves was not needed.

ULA aims for up to 20 missions in 2025, split evenly between its Atlas V and Vulcan rockets.

The most launches ULA has conducted in a single year to date was 16, in 2009. For perspective of recent cadence, ULA flew eight missions in 2022, three missions in 2023, and five missions year-to-date(Two Atlas V, a Delta IV Heavy, and now, two Vulcans). I wish them luck as they ramp Vulcan’s flight rate.

TREVORS TAKE

Building and flying a few test flights is one thing, but building up the rate of manufacturing, supply chain, and all other operations behind flying 20 launches a year of a combination of Atlas, Vulcan, or otherwise, is a considerable undertaking.

It’s not clear yet whether ULA or the FAA will consider this event an “anomaly” and require a formal investigation. The FAA said in a statement to several news outlets after the launch:

“The FAA is assessing the operation and will issue an updated statement if the agency determines an investigation is warranted.”

Update: the FAA has determined no investigation is necessary.

Surely, as important as Vulcan is to ULA’s future, Cert-2 is to the U.S. Space Force and Space Systems Command. More broadly, those protecting the national security of the United States will be curious too; several parties will want to get to the bottom of what happened.

What is clear, though, is that ULA will investigate the cause on its own and, similarly to the event in 2016, find out what happened “with the highest confidence of arriving at a complete, global, and permanent corrective action.”

It’s great to have leaders in the launch industry helping walk others through company announcements and anomalies like this, so candidly on Twitter. At present, there are almost too many of them to name in a succinct list, which makes it quite a time to be involved in spaceflight.

Congrats to ULA on the latest successful flight. Overcoming this will I’m sure take its toll, but as Vulcan steadied its roll, it demonstrated a robustness of ULA hardware and software that is quite remarkable.

Feature image by Trevor Mahlmann

SUPPORT MY WORK

Each of the photos and all of the writing in this story, is my own. I’m currently a self-employed photojournalist navigating my own uncharted territory.

If you’d like to see more stories like this, the best ways to support this passionate work of mine are to pre-order my Wall Calendars here or become a member!

Whether it’s via a comment, retweet, calendar order, or membership: thank you for your consideration and support! What I do wouldn’t be possible without your help.

Want stories like this in your inbox?

Leave your email below to keep up-to-date with the latest in spaceflight! (A few emails a month, max.)